Suffused in a predawn glow, Utah Lake conjures a particular enchantment. The sun has yet to tip its cup and spill golden milk over the Wasatch peaks, washing the valley clean of shadow. In the flux of periwinkle, past and future mingle with the present – guests at a pop-up tea party.

My gaze follows these meandering moisture marks stretching the length of the beach. In the distance a fuzzy figure, the future, waves from an arid, empty lakebed. It is an everyday apocalypse – one of many the future keeps in its back pocket.

Possibly, is its sole reply.

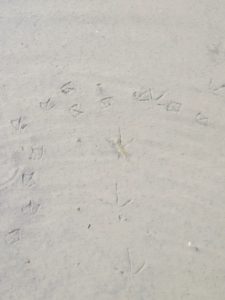

Turning back to the present, I attend to news from the night crew: impressions in the wet sand, disclosing the nocturnal activities of local fauna. Their footprints form an ever-evolving abstract, each creature contributing as brush, artist, and art.

Utah Lake itself is a footprint. Along with its sisters the Great Salt Lake and Sevier Lake, these dis-conjoined triplets are the progeny of a mammoth late Pleistocene inland sea: Lake Bonneville. I stand in its deep bed. The past suddenly rises before me, elevating the water’s surface to its epic peak. Nearly 300 meters above, the phantom titan expands, drowning the familiar landscape for hundreds of miles in its liquid reach. Like a child in a sandbox, it molds the earth, shaping the mountainous playpen. At last it overcomes its cradle, launching a centuries-long exodus, inscribing a geological signature extending from Southeastern Idaho to the Pacific Ocean. This dramatic breach marks the beginning of the end for Lake Bonneville. Time boomerangs forward. The climate grows hotter and drier. An epoch of aridification continues to diminish the primordial pluvial giant. Its evaporating body gives birth to the high desert lands of Western North America, until only the three remaining daughters are left in the wake.

All treading does not leave equal impacts. I reflect, following a set of prints that look like baby devil hands: raccoon. These diminutive impressions, punctuated at the tip by sharp little claws, grow faint in the shallows. I create competing wakes as I wade along. Within this rippling mirror, the past and the present grapple in similar confluence.

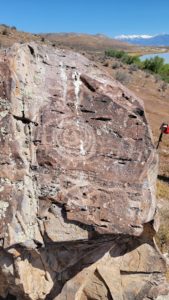

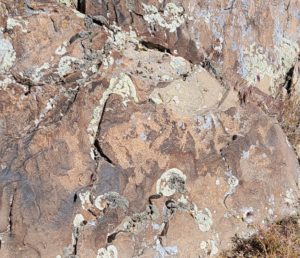

Lake Bonneville’s legacy thrived for millennia in robust ecosystems that evolved around its three remnant lakes. Situated against the border of North America’s desert lands, Utah Lake provided an invaluable freshwater resource for animals of all kinds. Petroglyph sites near the water indicate this lake has held a place of honor among indigenous peoples since prehistoric times.

Impatient, the morning slices through the twilight with a blunt yellow blade, illuminating the remains of several carp littered among paper products, plastic, and soda cans. With their bony mouths frozen into a defensive O, these morbid witnesses seem to form a dot-to-dot matrix of evidence and accusation. An invasive species, Cyprinus Carpio, was introduced to Utah Lake in 1882 after native populations had been fished to near extinction. This opening “environmental” intervention, committed on behalf of newly arrived colonizers, set the lake on an altered course. We, as antecedents and ancestors, are left to puzzle and reckon.

“It’s not your fault.” I assure the carp, answering the loud silence of their protestations.

The future, always the first to leave the twilight tea party, offers a nod. For a half second it holds my gaze. I see Utah Lake returning to health and abundance. Humans expand their efforts to reduce environmental loading. They recognize the lake’s intrinsic value, how it transcends, outweighs, and outlives shortsighted economic benefit. They become partners rather than puppet masters in its stewardship.

The future blinks. Utah Lake grows heavy, burdened by further pollution, disrupted by construction, misguided mitigations, and commodification.

Possibly, the future whispers, fleeing the sun’s chasing ribbons, disappearing back into the horizon of tomorrow.

Always retiring, the past recedes with less flamboyance.

A family arrives on the scene, returning me to the present. A handful of children run gleefully towards this natural water park. “Look, a seashell!” shouts one little girl. She offers up the spiraled shell of an ordinary pond snail. Her hair, tossing in a thermal breeze, forms a black halo, backlit by morning light.

I smile. The feather of hope lands softly.

If time is an arrow shooting ever forward, it does not fly straight. I am not a physicist, but something in me says it spirals. On the shaft of time, we travel around to meet again at certain places: crossroads, tipping points. If we have learned wisdom, we can use the experience gained in the past to nudge the future towards a better tomorrow – less distortion, tipping the scale in favor of creation and sustainability. A tomorrow in which Utah Lake is the jewel of Utah Valley, reflecting the sky, the trees, the animals, and us – part and participants with her.

Utah Lake Stories

Last fall I answered a call for submissions from Torrey House Press who put together this beautiful chap book and online edition in defense of this irreplaceable life giving resource; Utah Lake.

Last fall I answered a call for submissions from Torrey House Press who put together this beautiful chap book and online edition in defense of this irreplaceable life giving resource; Utah Lake.

I feel so honored to have had my non fiction narrative “Twilight Tea Party” selected to be included in the Digital Chapbook edition, under the subheading “Turn”.

Copies of this book and the digital edition are to be distributed to the Utah State Legislature in hopes that reading these selections will inspire the law makers of Utah to protect this lake as a natural resource and to advance policies that will continue to allow this lake to heal from years of human born and capitol driven mismanagement.

You can also purchase copies of Utah Lake Stories at Pioneer Book in downtown Provo.

You can also purchase tickets to attend a wonderful archeological tour of a cluster petroglyph panels along the west side of Utah Lake through the Smith Anderson Archeological Preserve.

And as always, happy wandering!

Juni-Jen

” width=”20″ height=”20″>